In the first part of this bisected article we saw some of the very worst tracks Formula One has had to offer. And yet, despite already having covered such famously bad circuits as Nivelles-Baulers, the elongated version of Bahrain and Caesars Palace, the annals of Formula One’s past and present have a great deal more to offer in the way of tracks that should never have been allowed to hold a Grand Prix. Let’s start in the present day…

Click here to discover more about the first five tracks on our list of shame.

5. Yas Marina Circuit

| Country | United Arab Emirates |

|---|---|

| Lap length | 3.451 miles/5.554 kilometres |

| Turns | 21 |

| Grands Prix held | 11 |

| Years | 2009 to present |

F1’s shiniest venue grew out of the desert – like the Caesars Palace Grand Prix before it – in the oil-rich United Arab Emirates to play host to the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, which it has now done for over a decade. For most of that decade, it has – like the Caesars Palace Grand Prix some time before it – been the Championship decider.

Like the Caesars Palace Grand Prix before it, track designers (in this case Hermann Tilke) had a completely blank canvas to work from, but without the same space constraints. Tilke could basically design whatever he liked and the money would be there for it. And he designed this mess.

The circuit is on Yas Island, a purpose-built piece of artificial land the exact shape required for the racetrack. Even in a sport renowned for its extravagances, this one is pretty remarkable. And yet, the circuit is hated by fans and drivers alike. When Charles Leclerc’s Race For The World event was drawn to have Abu Dhabi as its opening race, an entire lobby full of professional racing drivers (and Jimmy Broadbent) groaned as one at the prospect of it. As Kimi Raikkonen once described: “It has a couple of decent corners but the rest is shit.”

But it’s not just the circuit layout; on a circuit built from scratch on a piece of land designed around it, at the pen of the most experienced circuit designer Formula One has ever had and with an unlimited budget behind him, there are several areas where there was an abject lack of proper planning and preparation.

Great views, crap racing, sums up Yas Marina to a tee!

What should have been the circuit’s most spectacular overtaking opportunity – out of the high speed esses at 2, 3 and 4 into the hairpin at 5 – was given a great big wraparound grandstand so people could watch it. The issue was that this was where the runoff was supposed to be, and the compromise that was found was the slow chicane at 5 and 6 that makes the hairpin (now at 7) into in my opinion the worst corner in Formula One.

Not having learned from their mistakes, they did the exact same thing at the other end of that straight: Turn 8 was given a wraparound grandstand. Rather than change the circuit layout further, they instead cut a great big hole in the grandstand so that the run-off could go through it.

And then there’s the pit lane. Tilke left himself no room to put the pit lane, entry and exit on the start-finish straight, so he improvised by putting a big tunnel under the straight for the pit exit. Remember, unlimited money. While this kind of works, and definitely isn’t the worst pit exit on the calendar, it does rather draw attention to the missed opportunity of perhaps creating a figure-eight circuit on the site. It also means that the biggest bit of undulation on the whole track is the pit exit.

4. Montjuic Circuit

| Country | Spain |

|---|---|

| Lap length | 2.350 miles/3.790 kilometres |

| Turns | 12 |

| Grands Prix held | 4 |

| Years | 1969, 1971, 1973, 1975 |

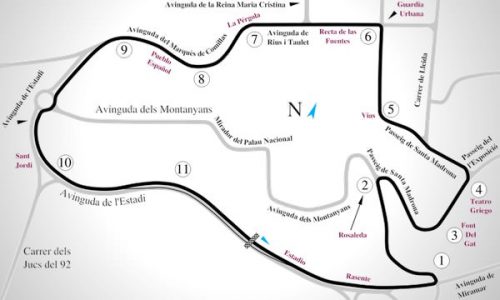

Of all the rash decisions made in the history of Formula One, the one to hold the 1969 Spanish Grand Prix on the narrow streets of Barcelona was certainly one of them. Montjuic was a circuit characterised by long, sweeping bends, lengthy stretches of full throttle, and absolutely no room for such luxuries as run-off or really any kind of safety. Despite only receiving fourteen entries, the 1969 race saw two enormous accidents as the always-fragile Lotuses fell to bits, causing high-speed crashes for Graham Hill and Jochen Rindt. This would be the last race where high-winged cars were allowed.

Montjuic plus a sprinkling of Colin Chapman-era Lotus was a lethal combination.

The 1971 race passed without significant incident, while the 1973 event was by many measures a genuine success as Fittipaldi and Follmer climbed through the field from seventh and fourteenth on the grid at the start to first and third at the finish. Even as the memories of the Hill and Rindt shunts retreated with passing years, it was becoming increasingly obvious that Formula One cars had outgrown the twisty little circuit.

Obvious to everyone except the Royal Automobile Club of Spain (RACE), who once again chose to host a Spanish Grand Prix there in 1975. It would see Jochen Mass’s only Grand Prix win and the only World Championship points ever by a female driver. These events were both made possible by 29 of the most destructive laps in Formula One history.

Before the race even got underway, two-time World Champion Emerson Fittipaldi had seen enough: he refused to set a hot lap in qualifying, setting a 2:10.2 that put him more than three quarters of a minute down on pole. He then also refused to take the start on the grounds that the circuit was a deathtrap. He wasn’t wrong.

Arturo Merzario, who had also refused to set a representative lap in qualifying, and Emerson’s brother Wilson Fittipaldi both completed a single lap of the race before pulling into the pits and retiring healthy cars. By this point, Lauda and Depailler were both also out of the race as a result of the race’s first collision.

Worse was to come as Donohue and Jones collected each other on lap three. Then James Hunt had a shunt on lap eight. Mario Andretti must have been having kittens when his suspension failed on lap 16 as a result of the bumpy Spanish streets, as must Tom Pryce when he crashed on his own ten laps later. But so far, nobody had been injured. Somehow. But it was clearly a matter of time.

When the Hill of Stommelen crashed from the lead, his rear wing having given up under the constant assault of vibrations from the track, his car speared into the same bit of armco that he had earlier asked his own mechanics to reinforce after spotting that it was a hazard. Their repairs held, and his car deflected off it and up into the crowd. Five spectators were killed, but somehow not Stommelen. His wrecked car is one of the most infamous photos in F1 history.

While spectators lay dying next to the track, a maybe-marshal ran onto the track and kicked Stommelen’s lost wing to the side of the road. Yet the racing carried on for another four laps, during which Mass made a pass for the lead, before someone finally had the sense to put a halt to the madness.

The Spanish Grand Prix never went back to Montjuic.

3. Zeltweg Airfield

| Country | Austria |

|---|---|

| Lap length | 1.988 miles/3.199 kilometres |

| Turns | 4 |

| Grands Prix held | 1 |

| Years | 1964 |

The 1963 Austrian Grand Prix, a non-championship event held to prove that the Zeltweg Air Base was a viable option for a Championship race. It did exactly the opposite of that: Jack Brabham won by five laps as car after car was shaken to bits by the uneven concrete patchwork that made up the track surface. Even the fifth-placed Lotus of Bernard Collomb was one of several DNFs owing to suspension failure. Kurt Bardi-Barry, a local driver who would be killed in a road accident less than a year later, voluntarily withdrew from what would be his only Formula One appearance.

Lorenzo Bandini, the only man to come away from Zeltweg with fond memories…

Upon viewing this, the Austrian Automobile Club clearly thought “Yes, that’s where we want to hold our Championship Grand Prix.” So they did.

In that 1964 race, Jochen Rindt made his Championship bow racing for Rob Walker and Lorenzo Bandini took his maiden (and sadly last) Championship win. He was one of nine finishers… sort of. Brabham’s Brabham saw the chequered flag, but it was 29 laps down and broken. Baghetti and Hailwood also limped in nine and ten laps down respectively. The track was by this point littered with broken bits of suspension and parked cars, but this did help Bob Anderson to claim his only career podium in his self-entered DW Racing Enterprises Brabham. On the bright side, nobody died; on the downside, the Austrian Grand Prix would cease to exist for the next six years.

2. Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps (original layout)

| Country | Belgium |

|---|---|

| Lap length | 8.761 miles/14.099 kilometres |

| Turns | 21 |

| Grands Prix held | 18 |

| Years | 1950-1970 (excluding 1957, 1959 and 1969) |

This is almost undoubtedly a controversial pick, but Old Spa was garbage. It was considered a particularly “fearsome” track in an era when Jackie Stewart was able to count 57 friends and acquaintances who had died at the wheel during his career. Stewart himself was so nearly one of them, stranded upside down and soaked through with flammable fuel for 25 minutes while the race went on without the seven drivers who had crashed out of the race on the opening lap. Had Bob Bondurant and Graham Hill not also crashed nearby, chanced upon the stricken Stewart and been able to free him with a tool kit that they borrowed off a spectator who happened to have one, or had any of their tools created a spark during that rescue effort, then the consequences of that accident don’t bear thinking about.

The eight who remained would drive with the utmost caution, simply surviving as opposed to racing in the Belgian rain, and only two cars would finish on the same lap as one another. The opposition wasn’t made up of the other drivers, it was the track, the rain and the reaper.

If you lost control here, you were either going into the spectators, the rubble pile or the side of the house. Doesn’t really bear thinking about, if we’re honest.

Like the Nurburgring, the track was far too large to marshal properly, such as marshalling even was in that era of racing. It was the first circuit at which the drivers collectively boycotted a race: the 1969 Belgian Grand Prix never took place. This would later also occur at the Nurburgring in 1970, when the race was hastily relocated to the Hockenheimring instead.

Many factors combined to make Spa so deadly. Its fourteen-kilometre length was one; if a driver crashes in the woods and no-one hears them, do they make a sound? Another was the fact that is was almost entirely flat-out. Aside from the La Source hairpin, few other corners on the track required heavy braking: this isn’t to say they weren’t dangerous or challenging in 300 hp, 450 kg machines with no downforce and narrow, bias-ply tyres. It’s just to say that if you braked too heavily you could get rear-ended. But if you didn’t brake enough, you were liable to go into the side of somebody’s house.

Old Spa also played host to the bloodiest race weekend in Formula One history. Not the one everyone thinks of, the one that was worse. In 1960, there were four separate events, each seemingly more horrific than the last. First, Stirling Moss lost a wheel at high speed in practice. In the resulting impact, he broke both his legs and in his own words “hardly could breathe because of course I’d broken my back”. Moss would recover to race again, which is more than could be said for Mike Taylor, whose steering column snapped at 160 miles per hour. His car rolled, and threw him from it; the force of his impact with one of the trees lining the circuit felled said tree, as well as breaking several bones and paralysing him. But the race must go on, and so it did. On lap 20, Chris Bristow lost control of his car and was thrown from it, over an embankment, and into a barbed wire fence, which beheaded him. Still the race went on, even when Alan Stacey hit a bird on lap 25 and crashed out. He was trapped in the resulting wreck and burned alive.

Old Spa was everything that was wrong with the era when young men were sent off to race because there was no war to send them to, even if it is now often fetishised by people who will thankfully never experience the horrors of racing on it.

1. AVUS

| Country | Germany |

|---|---|

| Lap length | 5.157 miles/8.299 kilometres |

| Turns | 4 |

| Grands Prix held | 1 |

| Years | 1959 |

What would you get if you took all the speed and danger and stupidity of Old Spa, took away all the nuance, and threw the Monza banking at one end of it?

The answer, of course, is AVUS – the circuit with the most “huh?” track map in Formula One history. At least the Nurburgring and Spa had corners and things; AVUS just looks like a motorway with a loop at either end for cars to go back whence they came. And that’s because that’s exactly what it was: a chunk of the Autobahn with a small diversion so that the cars could climb the steepest banking ever used in motorsports. It was big, stupid and deadly.

The Formula One version was a cut-down version of the track. A long-held explanation was that the Iron Curtain crossed the Autobahn halfway down the circuit, which has since been debunked. (Un)fortunately, the end that remained was the end with the infamous “Wall of Death” banking. Referring to it as such seemed rather like tempting fate, and indeed it was, but what was really tempting fate was building the world’s fastest race track without the slightest safety precaution.

At the 1959 Grand Prix, the Wall really did live up to its name when 38-year-old Frenchman Jean Behra’s Porsche overcooked the banking and went straight over the top.

Alexa, define “insanity”.

The top of the banking had not even the idea of a protective fence.

Behind the banking were eight huge flagpoles; Behra was thrown clear of his car and headfirst into one of them. It was sent toppling when Behra flew headfirst into it, and both car and lifeless driver fell to the ground in the paddock area where mechanics often worked on the Grand Prix cars. I cannot find a source anywhere that tells me which nation’s flag fell as Behra lost his life.

The amount of thought which went into the layout could be measured in femtoseconds…

But this was Formula One, and the race must go on. Or… races, as it was tradition at AVUS for races to be held over two heats with results decided by aggregate times. During said race, the only genuinely interesting thing to happen was the catastrophic high-speed crash of Hans Herrmann, whose BRM was sent catapulting and disassembling through the air. When everything came to rest, Herrmann stood up and dusted himself off, unscathed but for the surface-deep injuries one would associate with a slide along the pavement. Beyond that, there was little of interest: the second heat saw only nine cars take the start after six retirements in the first.

For sheer lack of sense, safety or sustainability, AVUS has to be the clear number one on this list. It is the epitome of the brazen ’50s disregard to death.

You must be logged in to post a comment.