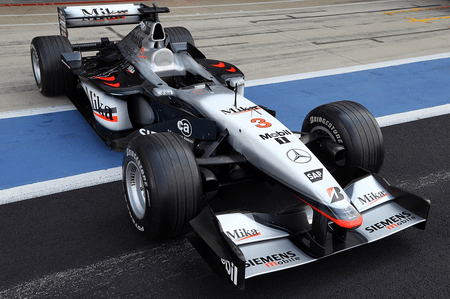

The 2001 Formula One season was one that drew in a lot of hype before it even began. Michael Schumacher, fresh off his third world championship and Ferrari’s first in over two decades, was faced with established competition in the top-class pairing of Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard in yet another Adrian Newey-designed McLaren. Furthermore, the two established top teams were about to be joined by a third contender-in-the-making as Williams, after a few down years, were in another works deal and the BMW P81 engine looked like one of or even perhaps outright the strongest power unit on the grid. New Michelin rubber was sure to be a game changer and the lineup was very promising: Ralf Schumacher, who had forced himself into debates about the best drivers in the sport in 1999 and 2000, was joined by 1999 CART champion and 2000 Indianapolis 500 winner Juan Pablo Montoya.

While Williams did not quite manage to make good on their potential early in the year on account of technical problems and driver errors (despite Ralf Schumacher winning the San Marino Grand Prix), McLaren looked ready to bring the fight to Michael Schumacher. After driving his way up the order from his seventh-place starting position to win the 2001 Austrian Grand Prix, David Coulthard was in as good a position as you could ask for. Having just turned 30 and therefore being in the prime of his career, only four points separated the Flying Scotsman from the Red Baron at the top of the standings after the conclusion of the sixth Grand Prix of the year.

Of course, as history would show, that margin would not stand. Eventually, Michael Schumacher won his fourth world championship by an extreme margin of 58 points. This is a historic change of fortunes for the worse: using a normalized 10-6-4-3-2-1 points system, there have only been six occasions in Formula One history where a driver was five or less points behind the championship leader or has been the championship leader outright after the sixth Grand Prix of the year, yet ended up more than 40 points behind the eventual champion.

| Year | Driver | Pts. margin after 6th race | Final points margin |

| 1979 | Patrick Depailler, Ligier-Ford | 5 | 40 |

| 1980 | René Arnoux, Renault | 0 | 45 |

| 1980 | Didier Pironi, Ligier-Ford | 5 | 43 |

| 2001 | David Coulthard, McLaren-Mercedes | 4 | 58 |

| 2012 | Mark Webber, Red Bull-Renault | 0 | 42 |

| 2018 | Sebastian Vettel, Ferrari | 5 | 46 |

Looking at the other five seasons, you can find clear context in both: Patrick Depailler did not even appear in any Grand Prix after the Monaco Grand Prix after turning hand gliding into leg breaking. René Arnoux and Didier Pironi were driving boxes of fireworks around the racing circuits of the world and after the sixth Grand Prix of the 1980 season, the two of them combined (!) for a total of five more points finishes (despite also scoring four pole positions in that same time period). Mark Webber was an overperforming number-two driver who profited from the chaos of the early 2012 season to launch himself up the standings; him dropping down the order was inevitable, once Sebastian Vettel and Fernando Alonso had made the championship battle their own (though he did not help himself with a truly terrible five-race stretch from Germany to Singapore) and Sebastian Vettel had to overdrive his car to make up for development and atrocious strategy mistakes by Ferrari, which compounded late in the season when he was forced to take excessive risks.

No such simple explanation exists for David Coulthard: while the MP4-16, like all Newey-designed cars, could occasionally experience technical issues (the most famous being Mika Häkkinen’s last-lap retirement at the Spanish Grand Prix), it was not outrageously unreliable like McLaren’s 2005 challenger. Furthermore, while Ron Dennis preferred Häkkinen, the Finn was clearly mentally exhausted after three seasons battling for the crown and had a total of four points to his name after Austria. It would have therefore made no sense for McLaren to not put their entire operation behind Coulthard, so that explanation is also not helpful in determining how this major defeat came to be.

No such simple explanation exists for David Coulthard: while the MP4-16, like all Newey-designed cars, could occasionally experience technical issues (the most famous being Mika Häkkinen’s last-lap retirement at the Spanish Grand Prix), it was not outrageously unreliable like McLaren’s 2005 challenger. Furthermore, while Ron Dennis preferred Häkkinen, the Finn was clearly mentally exhausted after three seasons battling for the crown and had a total of four points to his name after Austria. It would have therefore made no sense for McLaren to not put their entire operation behind Coulthard, so that explanation is also not helpful in determining how this major defeat came to be.

This leaves one question: what in the name of the racing gods happened?

To find out, the Gravel Trap will take a dive into the seven races between Austria and Hungary (the race Michael Schumacher had sealed his fourth championship) that turned a tight championship battle into one decided with four Grands Prix to spare.

#1 – Monaco Grand Prix – May 27, 2001

After Saturday, it seemed certain that Coulthard would tie Michael Schumacher at the top of the world championship (though Michael would have been ahead on countback). The Monaco street circuit is infamous for how important qualifying is and David Coulthard was ahead of his main rival by two tenths and one thousandth of a second. His second pole position of the season could perhaps prove to be the most important one of his career. Warm-up on Sunday only added to that impression, as David again led the time sheets. If McLaren staff were already mentally adding the ten points to their tally, nobody could have blamed them.

Unfortunately, on the start of the formation lap, everything broke down.

Coulthard’s car could not get going on account of a launch control glitch and he could only angrily raise his hands as 21 cars rolled past the stock-still McLaren. Alan Jones voiced his frustration on Channel 9 coverage and pretty much every Coulthard fan must have been at least equally upset.

He could get his car going, but by that time he was forced by the regulations to take the 22nd place on the grid. The first stage of the race was not too bad: by lap three, Coulthard was already back up to P18. Unfortunately, then he ran up to the back of the cars that would spoil his afternoon: the orange menace of the Arrows. After Jos Verstappen got by his teammate, Enquire Bernoldi made it his mission to hold David Coulthard behind them. That mission would prove successful beyond imagination. It took Coulthard almost 40 laps to outlast the Brazilian, hindering Coulthard’s comeback massively.

Bernoldi fought bravely, though it could be fairly argued that he at the very least stretched the actions permissible by the rules with his defensive driving. Later, Arrows would be accused of ordering Bernoldi to block Coulthard for the explicit purpose of getting television time. The author is inclined to believe those accusations, as much as Tom Walkinshaw tried to deny them, but sees absolutely no problem in that. Bernoldi did what he felt was necessary and did not explicitly violate any rules; any criticism of his is absolutely misguided and the Reject of the Race award given to Enrique Bernoldi by the old f1rejects.com site stands as one of their rare truly wrong award decisions.

Bernoldi fought bravely, though it could be fairly argued that he at the very least stretched the actions permissible by the rules with his defensive driving. Later, Arrows would be accused of ordering Bernoldi to block Coulthard for the explicit purpose of getting television time. The author is inclined to believe those accusations, as much as Tom Walkinshaw tried to deny them, but sees absolutely no problem in that. Bernoldi did what he felt was necessary and did not explicitly violate any rules; any criticism of his is absolutely misguided and the Reject of the Race award given to Enrique Bernoldi by the old f1rejects.com site stands as one of their rare truly wrong award decisions.

If anything, it must be asked why McLaren did not experiment with strategy. Of course, in the days of refueling, changing the strategy was not an easy task. However, Coulthard was losing around two to three seconds a lap in comparison to Michael Schumacher. One could easily make the argument that loading Coulthard up to the brim around lap 30-35 and having him run around in free air, even loaded with fuel, would have improved their chances of damage limitation compared to him idling around and saving fuel behind Bernoldi.

As it was, Coulthard made full use of the free air and got significant aid from a large number of retirements and an unplanned additional stop for Jean Alesi to at least get two championship points. With Michael Schumacher taking an easy win after Mika Häkkinen dropped from contention with technical issues, there were now twelve points between the two title rivals.

One could very well argue that the reaction of David Coulthard and McLaren to this race was much worse than the actual points loss. Both Ron Dennis and Mercedes-Benz head of motorsport Norbert Haug confronted the Brazilian over his defensive driving. Rumours of threats against the young Brazilian proved false, but the event was still a black eye to the reputation of the two men and this moment of shameful weakness – no other term is applicable, really – just emphasised the severity of the blow McLaren’s ambitions in both championships took.

In particular David Coulthard looked foolish and emotionally imbalanced by calling Bernoldi an “idiot”, given his own inability to pass the Arrows driver. Of course, by doing so he left an open goal for the avid soccer fan Michael Schumacher. He told Coulthard, to put it in blunt terms, to stop crying about it and move on. He pointed out, as the author did, that Bernoldi violated no rules. He understood Coulthard’s frustration, but felt such a heated reaction was not appropriate. By no means was Michael Schumacher a trash-talker in the mould of a Nelson Piquet, Sr. or a James Hunt, but he knew well enough how to pounce on an opponent who had shown such weakness.

If Schumi thought he had Coulthard under wraps, it would be quite hard to blame him.

#2 – Canadian Grand Prix – June 10, 2001

One reason the Monaco disappointment, besides the obvious loss of points, must have been so challenging for David Coulthard was the fact that Formula One was moving on to a track that very much was one of Schumacher’s best. The German had won on four occasions at the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve, once with Benetton and thrice with Ferrari. This, interestingly enough, came in spite of Michael Schumacher not actually liking the layout all that much.

Sure enough, Michael secured a relatively easy pole position by dominating affairs on Saturday by setting a lap time that was over half a second faster than the competition with twelve minutes to spare in the session. Coulthard finished third and the man in between the two would reveal a second problem for the Scotsman: Williams were back in the hunt as their powerful BMW engine proved crucial on the long back-straight. Ralf Schumacher started second to establish an all-Schumacher first row.

The start went harmless enough, the two Schumachers fought hard but not risky and Coulthard calmly maintained his third position. However, things would soon take a turn for the worse for McLaren. In a scenario Max Verstappen can only solemnly dream about, Michael Schumacher’s teammate, future Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year Rubens Barrichello, proved quite helpful for Schumacher’s chances by passing Coulthard for third.

As ITV reported on a possible problem on Coulthard’s car, the Scotsman could not quite manage to go the pace of the Schumacher brothers and Barrichello. The latter quickly removed themselves from the competition with a silly spin out of the last hairpin. As the German brothers continued their family feud, Coulthard just failed to keep up and was more occupied with keeping a quick Jarno Trulli in check. By lap 18, Coulthard was around 14 seconds behind race leader Michael Schumacher.

Once more, Barrichello unintentionally helped the Scotsman. His crash brought out the safety car and neutralised the field. It was clear that Coulthard had to try to make the most of this chance and fight his way past Ralf at any cost. However, despite the Michelin tyres struggling to pick up heat after the SC period, Coulthard could not come quite close enough to make a move at the hairpin and any slipstream assaults were denied by BMW’s superior top speed. Soon enough, Coulthard was well behind the Schumacher brothers, with his main job being to stop Jarno Trulli.

With Trulli unable to actually mount an attack, television mostly focused on the breathtaking war between Ralf Schumacher and his older brother at the top of the table. During his pitstop, James Allen informs us that Coulthard had to fight with overheating issues, which explained his problems. Surviving the threat of Jarno Trulli on his fresher tyres, he maintained his position with teammate Mika Häkkinen and Jos Verstappen ahead, but in need of another pitstop.

Häkkinen found himself out ahead of his teammate after the second stop. Before a team order could fix this little mishap, David Coulthard’s Mercedes-Benz engine violently blew up for Coulthard’s first retirement of the year. Coulthard could only look on in frustration as his distance to the championship leader would expand further. At least he could rely on Ralf Schumacher to drive the first place he got at the pit stops home for the first 1-2 finish by a pair of brothers.

Häkkinen found himself out ahead of his teammate after the second stop. Before a team order could fix this little mishap, David Coulthard’s Mercedes-Benz engine violently blew up for Coulthard’s first retirement of the year. Coulthard could only look on in frustration as his distance to the championship leader would expand further. At least he could rely on Ralf Schumacher to drive the first place he got at the pit stops home for the first 1-2 finish by a pair of brothers.

Unrelated: the author gives a dishonourable mention for Reject of the Race to the press conference interviewer for asking Ralf Schumacher, after he summarised the events of the race, whether it was “the most fun [Ralf’s] ever had with [his] clothes on”. Whilst certainly just meant to lighten the atmosphere, for sure, it does sound quite weird and creepy.

#3 – European Grand Prix – June 10, 2001

The story of this one is a story of practice performance not translating to qualifying: McLaren were immediately on the wrong foot for the legendary Nürburgring as David Coulthard only managed to start in 5th position, with both Ferraris and Williams ahead.

A minor glimmer of hope came up when Michael Schumacher was forced to switch to the spare car as his main drive broke down on the outlap. Despite Ferrari’s misgivings, the German managed to start the lead with the T-car and keep P1, even if it meant being very aggressive against his own flesh and blood.

Barrichello failed to keep the McLarens behind, but that was the only car Coulthard would manage to get by. In the early stages, Coulthard was close to Montoya, but never close enough to make a move on the Colombian, who faced quite a lot of pressure within the team. Rumours talked about a possible return of Jenson Button to the British team to replace the underperforming Montoya.

The attention of the world was rightfully on the battle of the brothers, who actually were willing to fight for position. While Ralf Schumacher found no opening in the iron-clad defence of his brother, his ambition clearly contrasts with Coulthard’s unwillingness to attack the Schumachers in Canada. To emphasise just how hard Ralf Schumacher was pushing, he forced his way past Coulthard after the German made his pitstop. One could easily argue that DC would have gained nothing from fighting Schumacher for long, but the way he got passed still looked uninspired.

He got the place back eventually on account of Ralf Schumacher being awarded a ten-second stop-and-go penalty, very much to the annoyance of Australian Formula One colour commentator Alan Jones.

“They really know how to ruin a good Grand Prix these days, don’t they? I mean, just as things were lining up they wrap a penalty in.”

Unfortunately, this was actually a net loss in the championship as the sole threat to Michael Schumacher’s home win was gone, so the additional point for third was offset by a lost chance for Michael to lose four points. Martin Brundle correctly pointed out that the final third-place finish for Coulthard was a “save”, as the McLaren failed to really look competitive all afternoon.

Unfortunately, this was actually a net loss in the championship as the sole threat to Michael Schumacher’s home win was gone, so the additional point for third was offset by a lost chance for Michael to lose four points. Martin Brundle correctly pointed out that the final third-place finish for Coulthard was a “save”, as the McLaren failed to really look competitive all afternoon.

After the conclusion of this Grand Prix, things were looking troublesome in the championship for David Coulthard. He was now 24 points behind Michael Schumacher and his apathetic look on the podium during the trophy ceremony demonstrated that he cannot have been too pleased with his Nürburgring weekend. Still, there was no time nor justification for depression. 24 points is a lot, but not a death sentence by any means with a bit less than half the season still to go. There were, after all, eleven drivers in Formula One history (eight of whom achieved that feat before 2001) who were more than 20 points in a normalised 10-6-4-3-2-1 system behind the championship leader at any point after the third Grand Prix of the season and still went on to take the championship decision to the final race.

| Year | Driver | Largest pts. deficit |

| 1959 | Sir Stirling Moss, Cooper-Climax/BRM | 24 |

| 1964 | John Surtees, Ferrari | 23 |

| 1968 | Sir Jackie Stewart, Matra-Ford | 26 |

| 1976 | James Hunt, McLaren-Ford | 38 |

| 1986 | Nelson Piquet, Sr., Williams-Honda | 21 |

| 1994 | Damon Hill, Williams-Renault | 37 |

| 1996 | Jacques Villeneuve, Williams-Renault | 25 |

| 1998 | Michael Schumacher, Ferrari | 22 |

| 2006 | Michael Schumacher, Ferrari | 31 |

| 2007 | Kimi Räikkönen, Ferrari | 25 |

| 2016 | Sir Lewis Hamilton, Mercedes | 24 |

Obviously, this means that the story of David Coulthard’s championship challenge collapse is not fully written yet. The Gravel Trap will go into the deep dive on how Coulthard and McLaren’s hopes of winning the 2001 World Driver’s Championship fully turned to nothing next Saturday.

Sources: Autosport, BBC, Channel 9, motorsport-total.com, newsonf1.com, ITV

Image Sources: Paul Lannuier (licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, resized), Peter Wright (licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, resized), United Autosports (licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, resized), ZDF

You must be logged in to post a comment.